Is it fair for baroque to sound so sensual? An elegiac soprano

voice wafts above an instrumental piece by Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger.

Flamenco rhythms underpin a passacaglia. Then suddenly we hear the

typical harmonies and ornaments of Celtic folk music. Is that how this

music really sounded in Italy in the early 1600s? Of course not. But

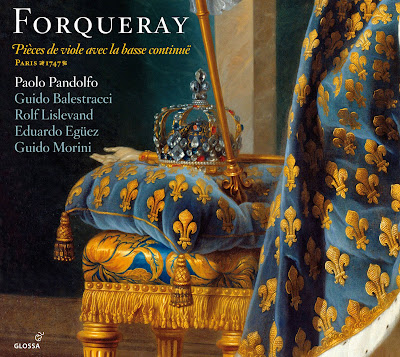

what the Norwegian lutenist and guitarist Rolf Lislevand and his six

colleagues bring off on

Nuove musiche, their début album for ECM,

has all the earmarks of a manifesto. Their vibrant and literally

unheard-of readings of early baroque music from Italy are meant to grab

the listener directly, as if it really were 'new music'.

'For years people tried to play early music as closely as possible to

the way it was played at its time of origin', Lislevand explains 'But

that's a philosophical self-contradiction. The first question is whether

it's possible at all to replicate the performance of a musician who

lived centuries ago. As far as I'm concerned, reconstruction is not

really interesting at all. Do we really want to act as if we hadn't

heard any music between 1600 and the present day? I think that would be

dishonest. With this recording we say goodbye once and for all to early

music's authenticity creed.'

This doesn't mean that anything goes - on the contrary. Lislevand, who

learned his craft at the famous Schola Cantorum in Basle, has been

professor of lute and historical performance practice at Trossingen

Musikhochschule since 1993. He has turned out many prize-winning

recordings, some of them with his Kapsberger Ensemble, which forms the

core of the musicians on Nuove Musiche. He avidly scrutinises every

available scrap of information on what he plays and how to play it

properly. But those are only the preconditions for a convincing

performance. After all, one vital element in baroque music was

improvisation: 'Pieces were played to meet the needs of the moment',

Professor Lislevand points out. 'To play strictly according to the notes

on the page would be tantamount to lying, for the scores were written

in a sort of shorthand. They presuppose a good deal of knowledge and

self-assurance from the player.'

Take the percussion instruments, for instance. We know they were used,

but nobody around 1600 bothered to write down the parts. So we have no

way of knowing for sure how they were used. Did they only serve as

timekeepers, or was their timbre exploited as well? Lislevand has very

strong views on the subject: 'The idea that it wasn't until today that

we could freely express our feelings is not only naive but arrogant.

Personally I believe that the people of the 17th century were much

richer and more self-aware than we assume today.' It is only natural,

then, that the percussionist Pedro Estevan offers a huge range of

expressive sounds and rhythms on

Nuove musiche.

Lislevand searches for points of contact between the 400-year-old pieces

on this recording (by Kapsberger, Pellegrini, Piccinini and others) and

the musical horizons of today's performers. Usually the starting point

is the passacaglia, a set of increasingly dramatic variations on an

unchanging bass pattern. Passacaglias formed the core repertoire of the

lute and guitar books of the 17th century. 'They thrive on chromaticism,

harsh dissonances and offbeat rhythms. If the composers tried to get

these effects, then we have every right to go even further. My idea is

simply to develop and elaborate things already there in the material.

Arianna Savall's melody really does come from the Kapsberger toccata

itself. Everything there that smacks of echoes from current popular

music is already contained in the pieces. I just coax it out.'

(ECM Records)